In a distinct way my birthday had already proved pivotal for

my anthem tour. A year earlier when I had

sent out my requests to teams for pre-approval to sing the anthem, I had included

a link to a streaming video of me singing for a game between the Rockies and

Reds in Cincinnati on my birthday several years earlier. Like that day in Southern Ohio, this sunny birthday

in Erie would be a scorcher, with the temperature in the shade—if any could be

found—settling in the 90s and the humidity level, well, next to the Great Lake,

don’t bother to measure it.

In most of the grandstands and on the field, of course, the sun

proved tenacious, blistering fans and fielders alike. Although I try to be cool when I sing the

anthem a cappella, intense heat vies to accompany my performances. Already on the tour Bonnie and I had

encountered record high temperatures in Texas, Tennessee, and Alabama, and within

the next few days and weeks we would continue to swelter through another record-setting

heat wave sweating its way slowly across the Midwest. Even so, Erie’s singeing afternoon could not

match the on-field temperature on my birthday in Southern Ohio some years

earlier. Then on the artificial turf at

Riverfront Stadium, the game-time temperature had crested above 120 degrees, a

few degrees cooler, believe it or not, than two days before when a thermometer

on field had registered more than 130. A

vivid series of non-anthem images comes to mind when I recall that afternoon. After the fifth inning the batboys took a

liter of water to each of the umpires. Standing behind second base, one ump quickly

guzzled a portion, then removed his cap and splashed a little on his hair, and finally

poured the last half of the bottle in a circle around his feet, letting the

immediate evaporation cool his cramping legs.

In Cincinnati, I had been offered a chance to view the game

from an air conditioned suite where my college alumni group was holding a

reception. Yet in Erie the only shade

and breeze that we could find was in the row of seats in front of the open

broadcasters’ window, through which we could faintly feel the wafting of his

words past our ears. So there we sat in

semi-shade for several innings, enjoying his play-by-play descriptions and color

commentary, and imagining how we might have differently filled the long pauses

interspersed with action on the field.

Despite the scalding heat at birthday baseball games, my

anthem performances were well received.

As in Cincinnati, the Erie team provided me with a video of my

performance, only the third ballpark on the tour where I had received a DVD of

my rendition. The first had been in

Frisco, Texas, and the next in Winston-Salem.

In both of those cities new ballparks relished the chance to utilize their

sophisticated recording systems. By

contrast, Erie’s Jerry Uht Park seemed to emit aromas of history. So I was surprised at the stellar quality of the

video and sound systems, as well as the all-star caliber tech crew at this

urban ballpark, not simply because they recorded my performance but also because

they personalized my introduction with comments about my making a national tour

and celebrating a birthday.

Politely, the crowd preceded my rendition with applause, and

following my straightforward presentation of the anthem two fans approached me,

one with the familiar expression of appreciation that I had sung it as written

and another with terse praise: “You did a damn good job. That’s a hard song to sing.”

The sense of history that fans get at “the Uht,” as the SeaWolves’

ballpark is familiarly known, derives in part from its memorials, its

simplicity, and its street placement in an established neighborhood. Constructed in 1995 and renovated about a decade

later, the ballpark celebrates civic leadership and baseball achievements rather

than corporate sponsorship. The ballpark

did not auction naming rights to local enterprises or corporations. Adhering to an older tradition, it preferred

to be named for a long-time area resident who had established an endowment with

the Erie Community Foundation for the maintenance of the ballpark and support

of its operations.

|

| The Uht's urban setting bounded by commercial buildings behind third... |

|

| ... and an established residential area beyond left field. |

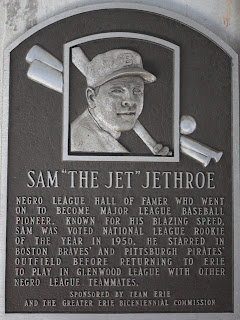

In addition to its recognition of Uht, the ballpark also achieves

a personal sense of history by displaying bronze steles of former Pennsylvania

Governor Robert Casey, who was instrumental in securing funding for the

ballpark’s construction; Dick Agresti, who was the founder of Erie’s Boys

Baseball, for which he built fields and organized volunteers to enrich the lives

of the areas youth; and Mike Cannavino, who was a mid 19th-century city

council member responsible for saving the Erie Sailors (the SeaWolves’

predecessor) for the city.

|

| Jethroe's plaque. |

Jethroe’s number 5 is also one of only two displayed on the

outfield wall. When I saw the baseball with his name and number, I asked a staffer who he was and why he was associated with Erie. She didn’t know but

suggested that the memorial was from long ago.

(I discovered Jethroe’s identity a few innings later when I photographed

the series of plaques in the undercroft of grandstands.) The other honored number in left field is uniform,

Jackie Robinson’s 42—uniform both in the sense that it was the numeral on his jersey,

and uniform in the sense that it is the single number retired throughout the

Major and Minor leagues. Curiously then,

the only honored numbers at Erie are for former Negro League stars who became

Major League pioneers yet who never played for an Erie professional team.

|

| The outfield numbers of Robinson and Jethroe. |

Even though kids at a 21st century ballpark might

not seem to be drawn to history and its traditional practices, the children at

Erie this afternoon enjoyed their time at “the Uht” in old-fashioned ways. Without the lure of techno-pitches and swings

or the chance to careen off the walls of

bouncy rooms, they anticipated foul balls with eyes glued toward home and

gloves poised, and later they lined up for the simplicity of a

run from the centerfield fence across the first base line during a between-inning

dash known as “Kids’ Stampede.”

|

| Kids ready to catch a foul ball. |

|

| Kids stampede across the outfield between innings. |

There is also other, hidden evidence at the ballpark that

contributes to its historic aura: its left field foul pole. Routinely at ballparks, I tried to take a

photograph looking from a foul pole down the line to home plate. That perspective occasionally provided distinct

pictures. When looking at the shot that

I had taken from beyond the left field fence at “the Uht,” I discovered that rusty

holes had pocked the pole as though it had endured more than twenty

winters. I also saw a fascinating

difference in the construction of the pole: a gap of six to eight inches

extends above the fence and below the “fair screen,” which aids umpires in

making the right call of “homerun” or “foul” on long drives that clear the

fence. I wondered if a ball had ever

been hit through the gap, avoiding hitting the screen and causing an ump to

call a homerun “foul”!

|

| The rusty view through the gap of the left field foul pole. |

I wouldn’t be so lucky that afternoon to witness such a

rare feat, even though Diek Scram did hit a homer for the SeaWolves in their 9-3

victory over the Curve.

No comments:

Post a Comment